Abstract

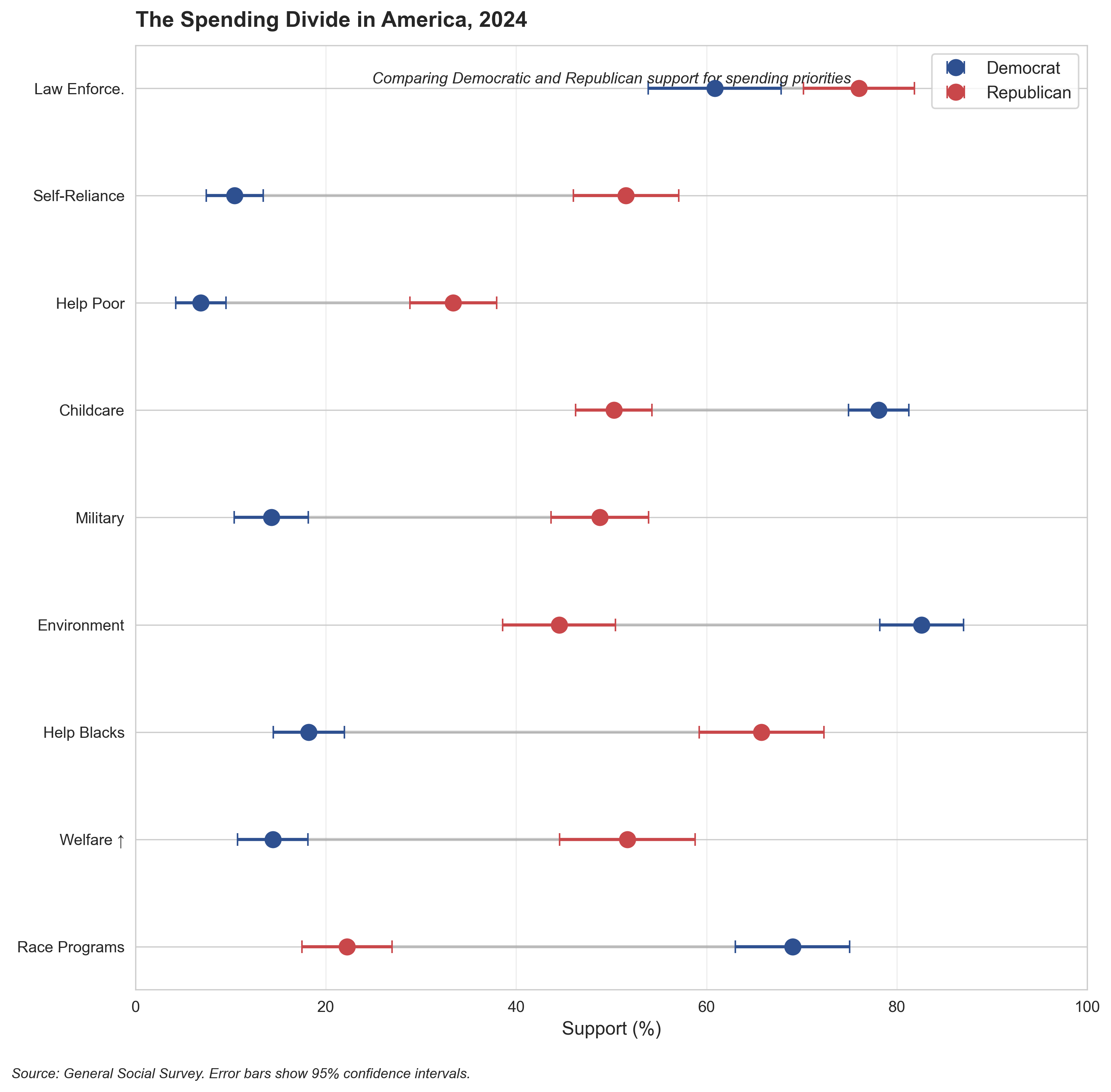

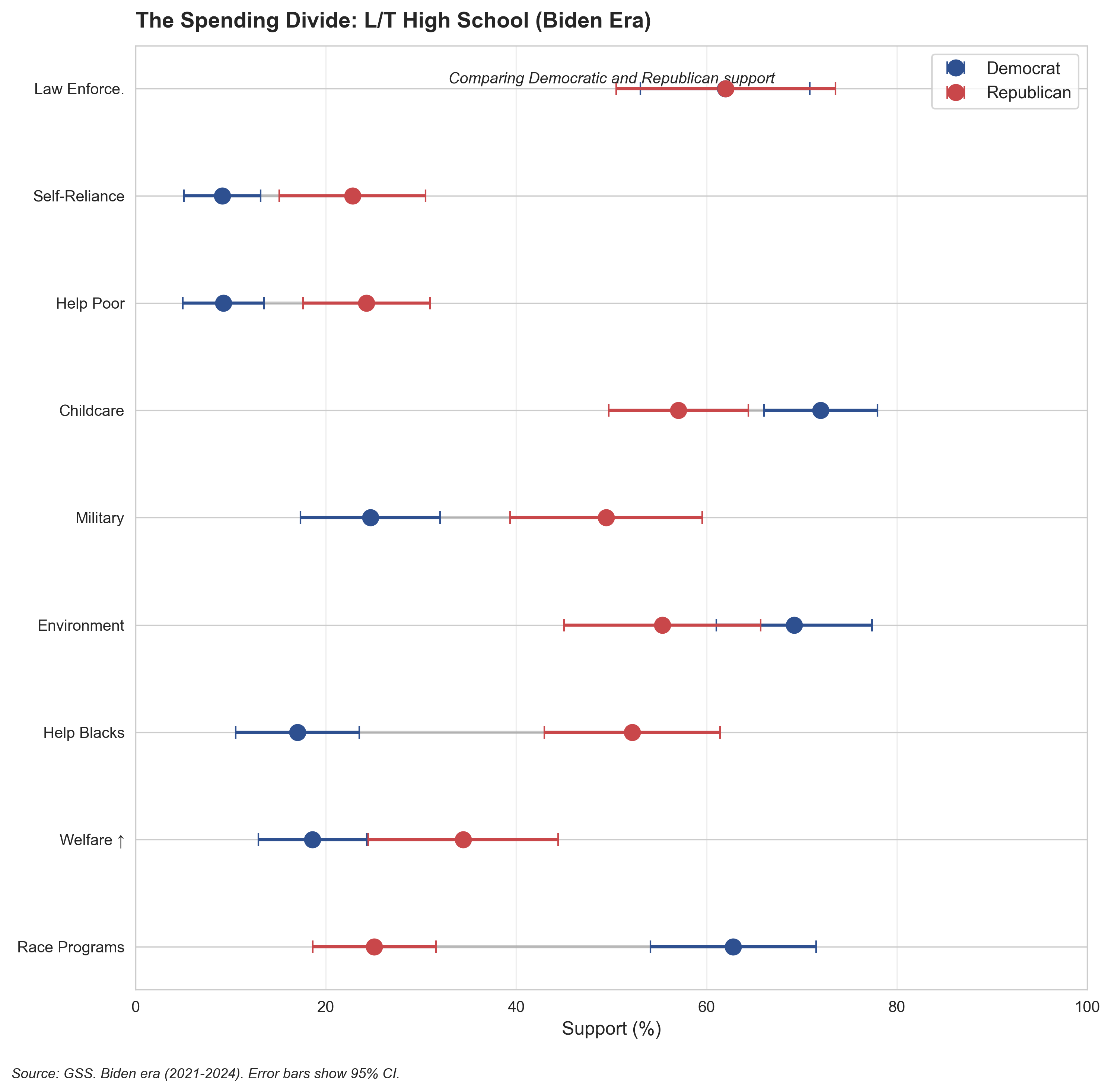

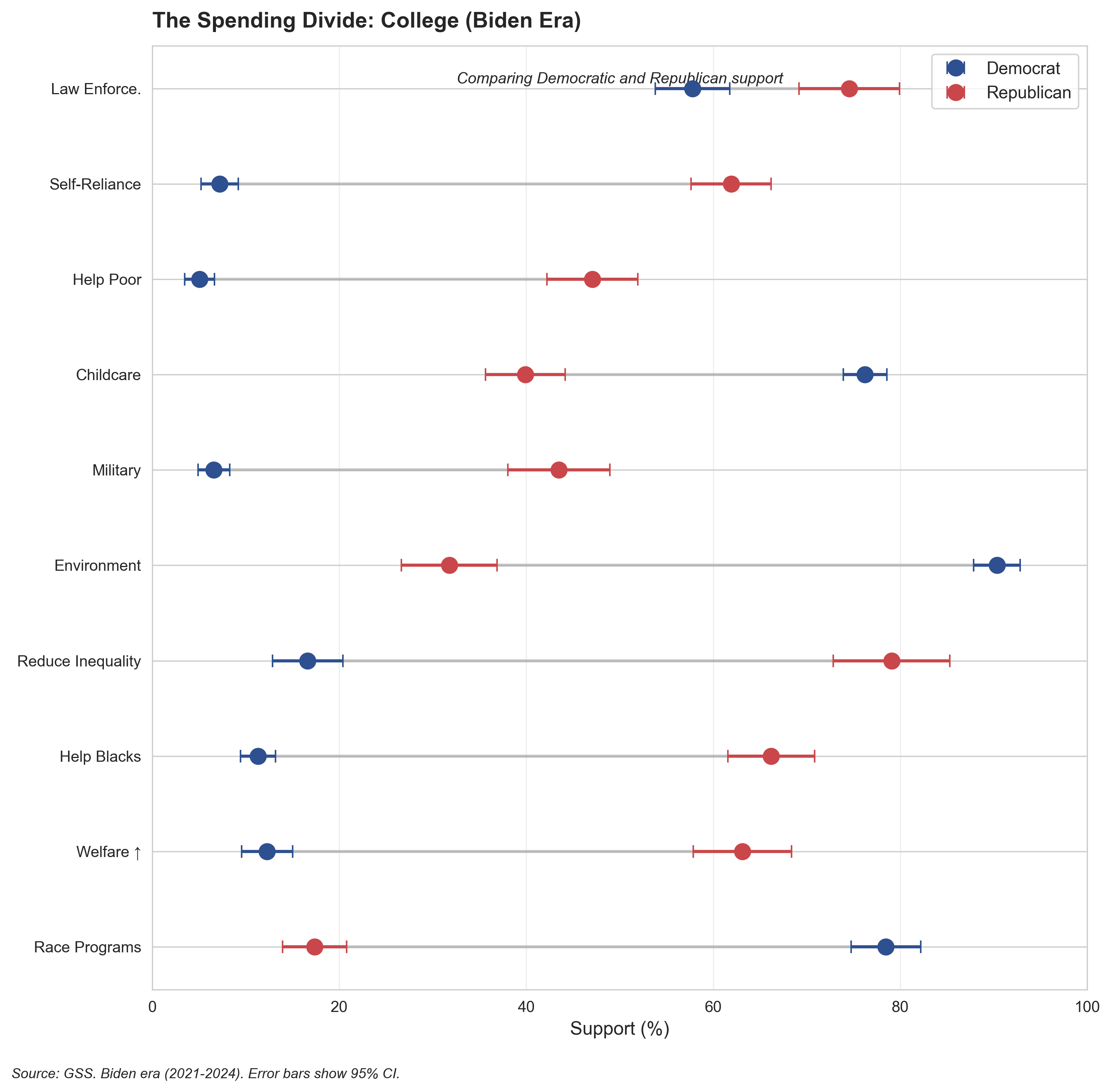

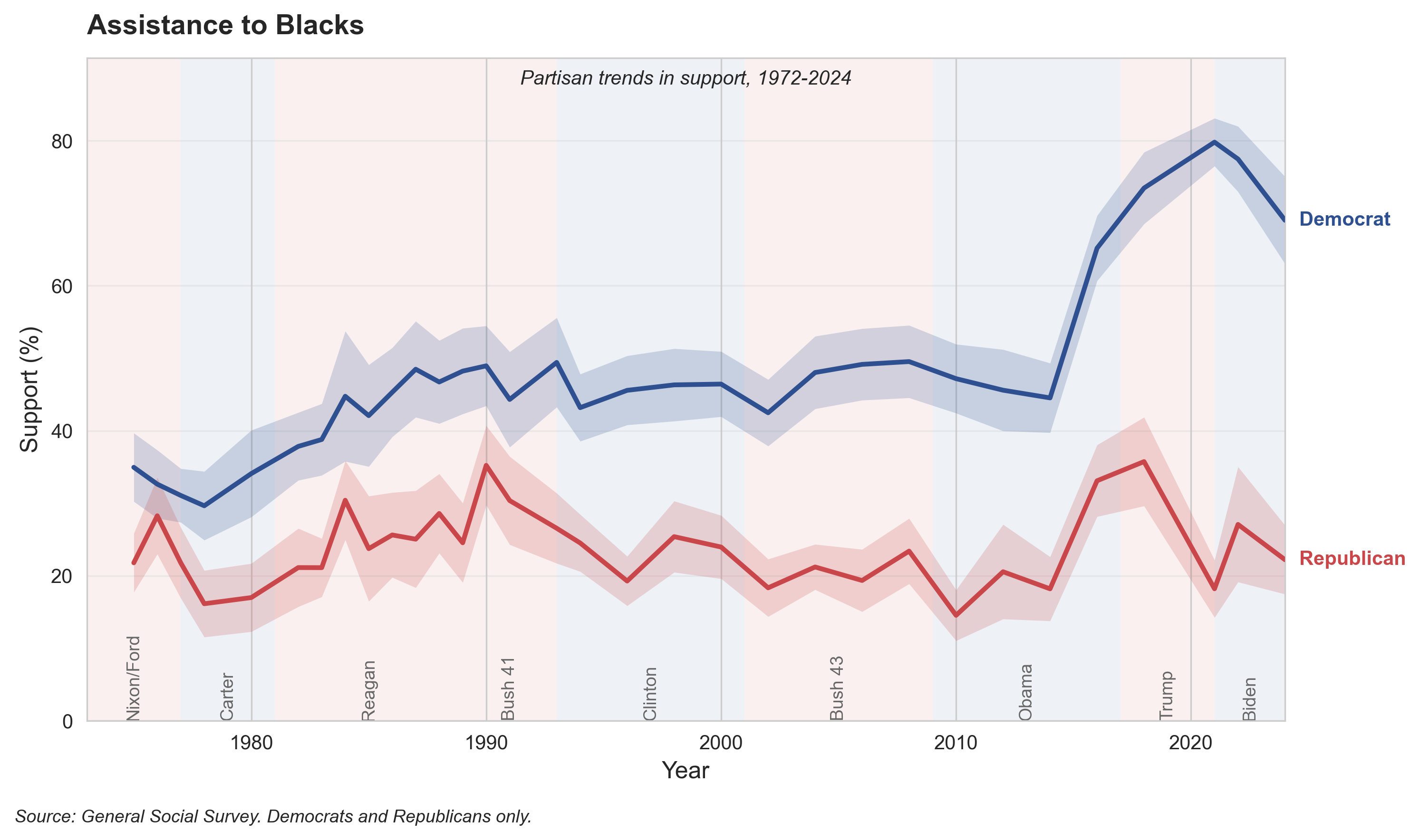

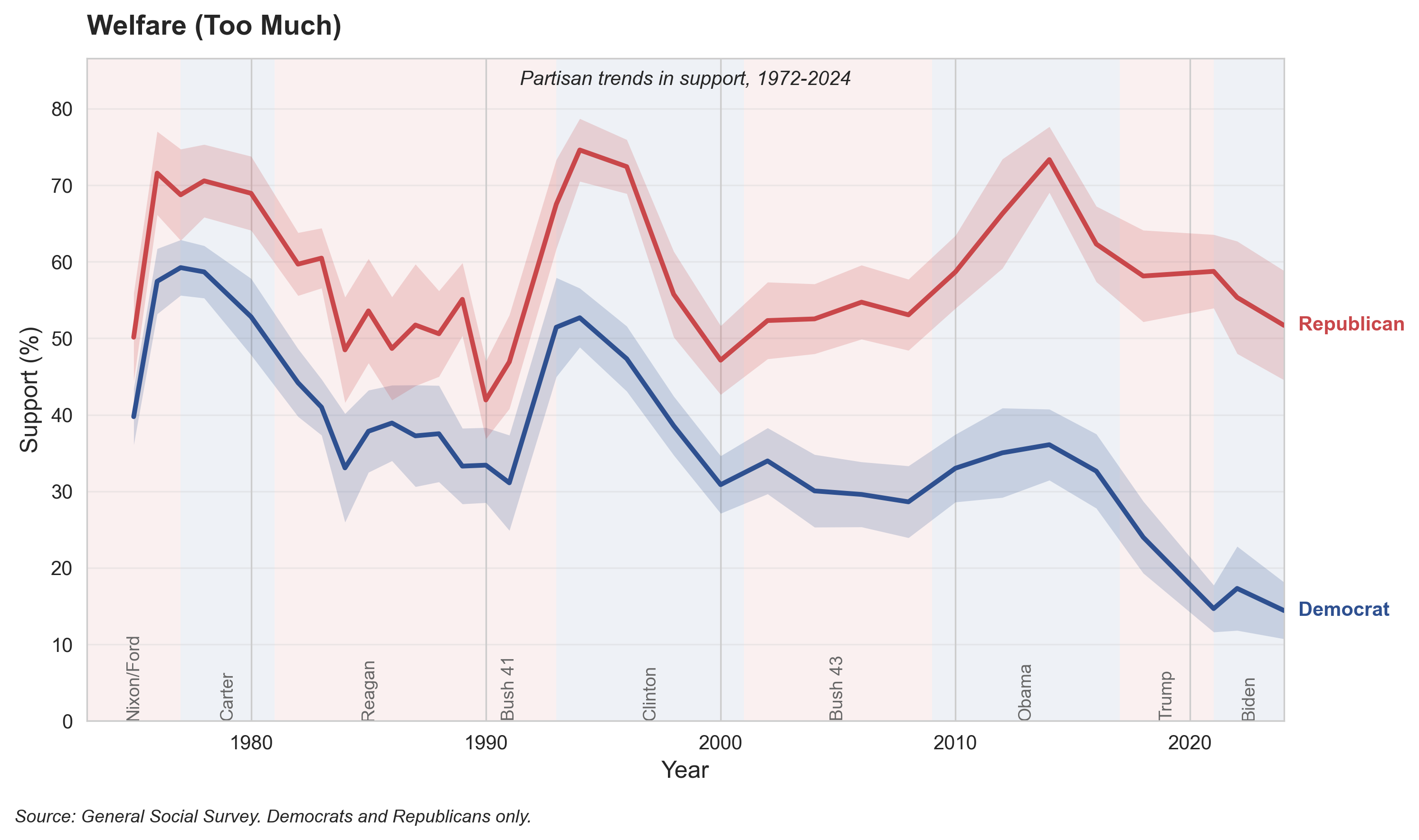

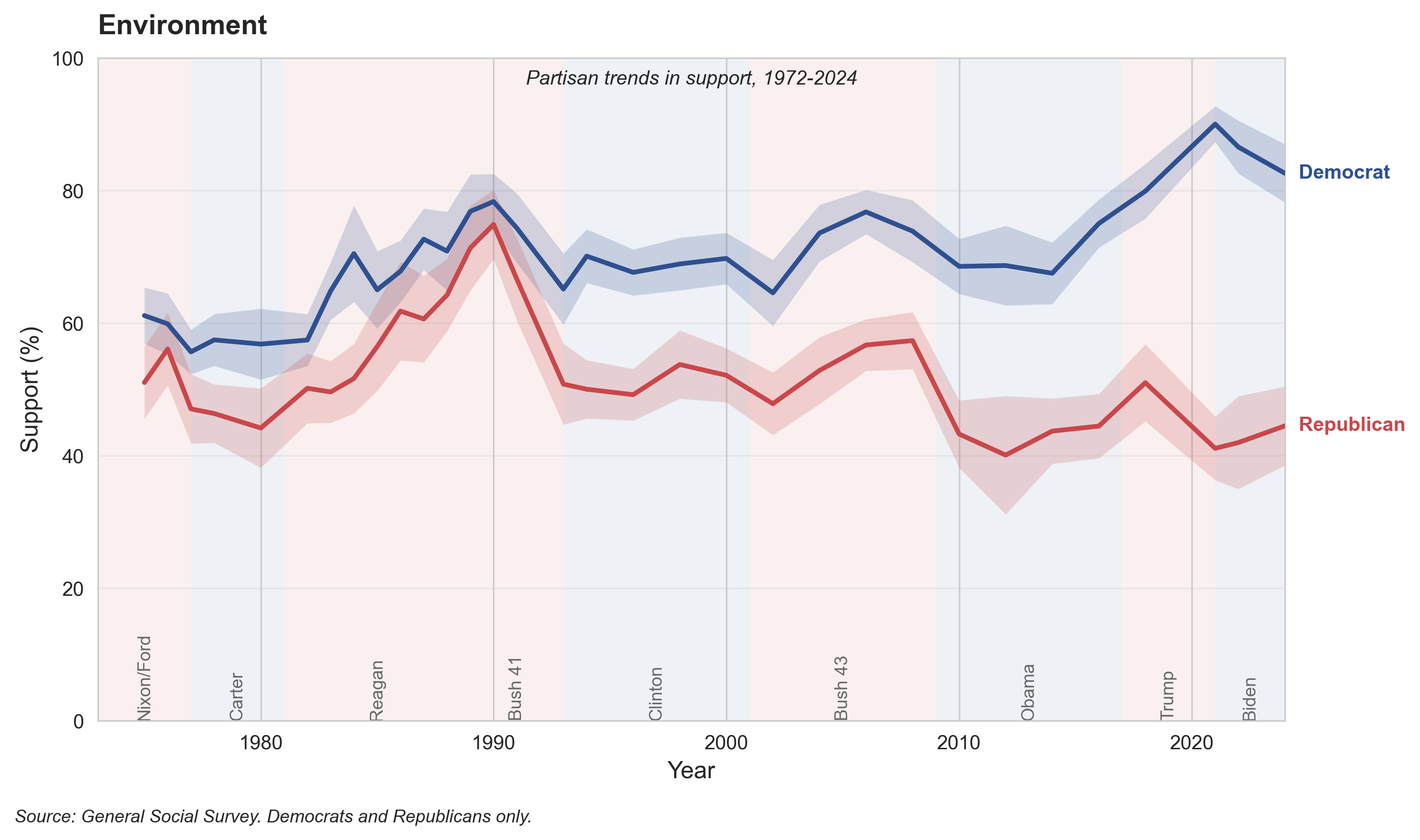

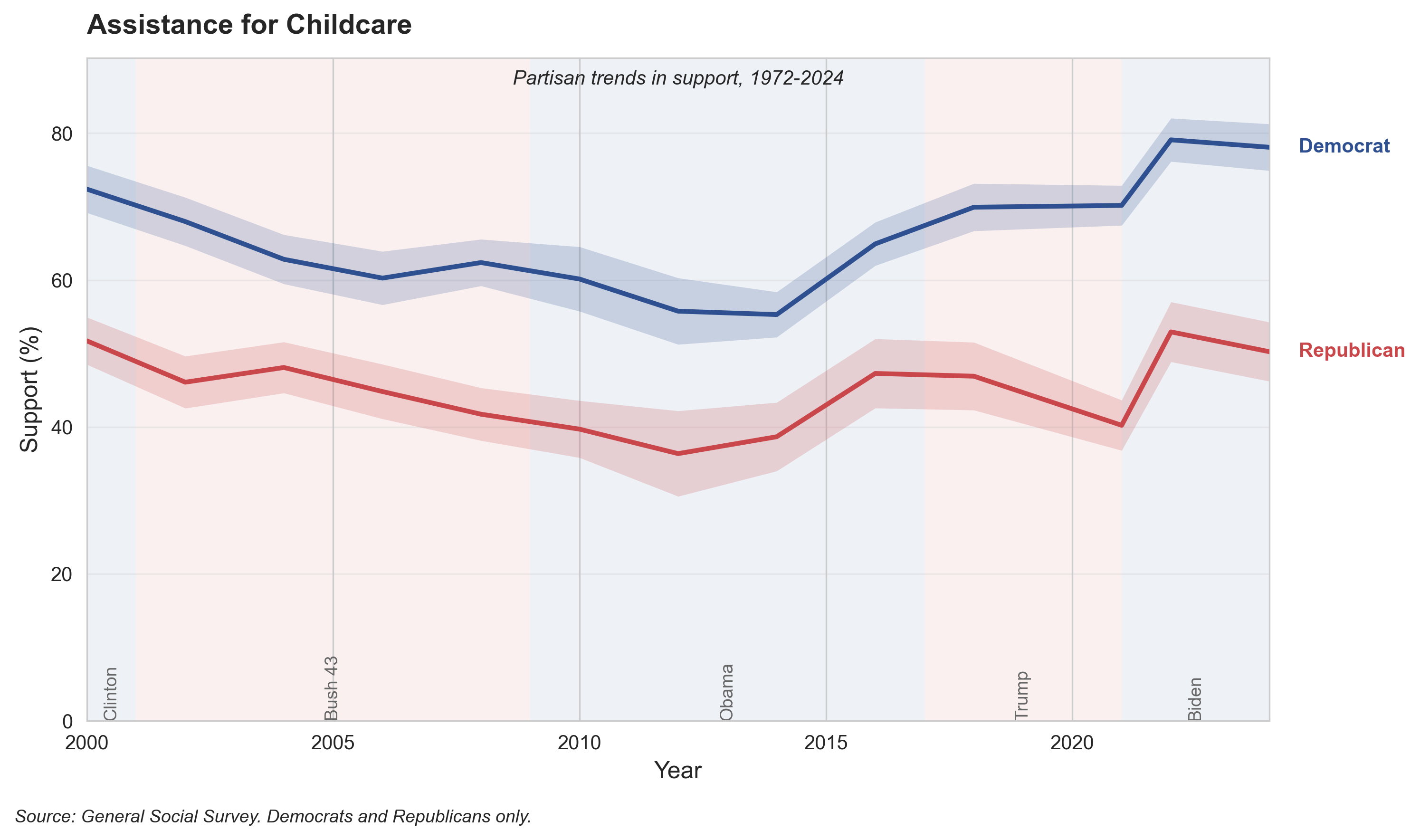

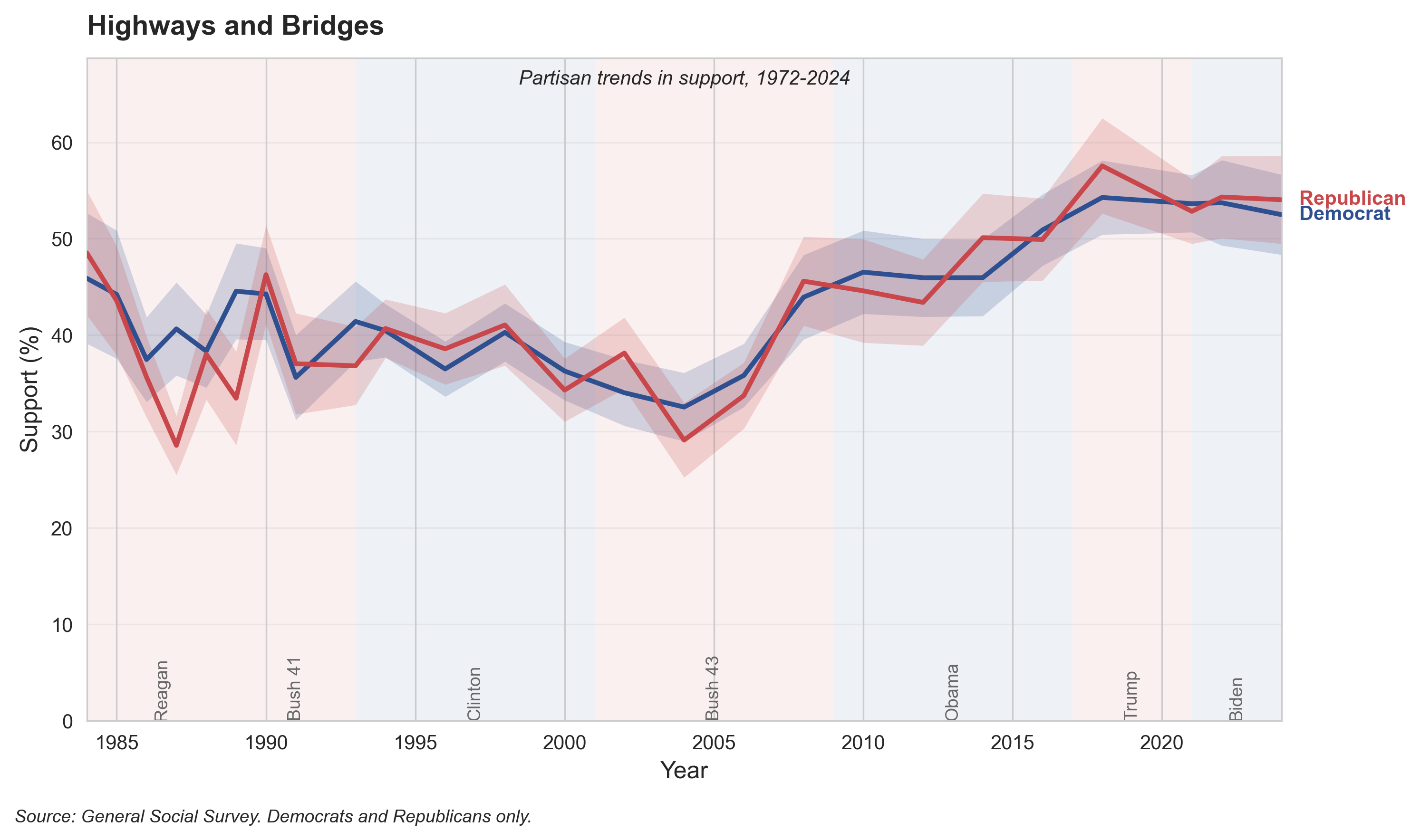

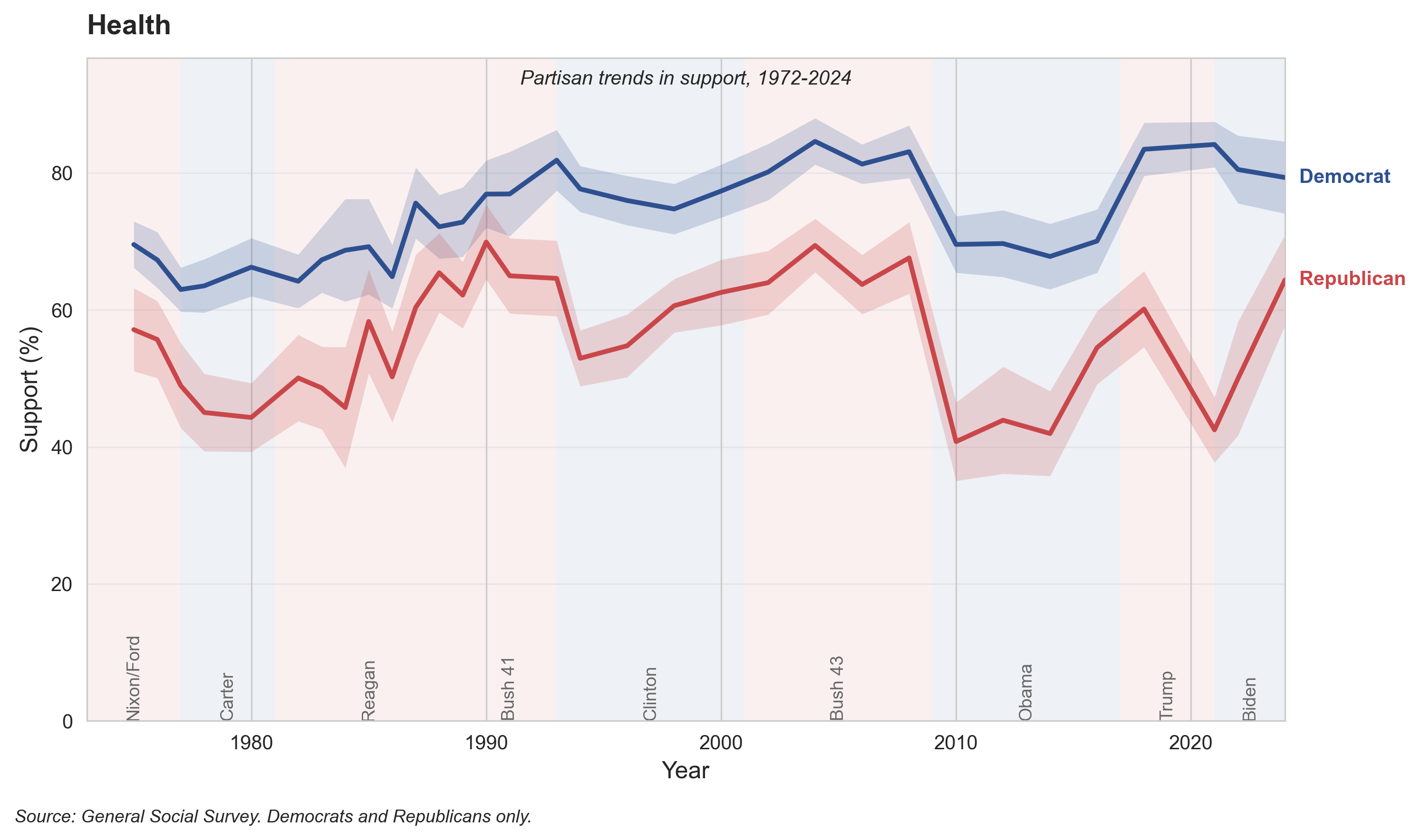

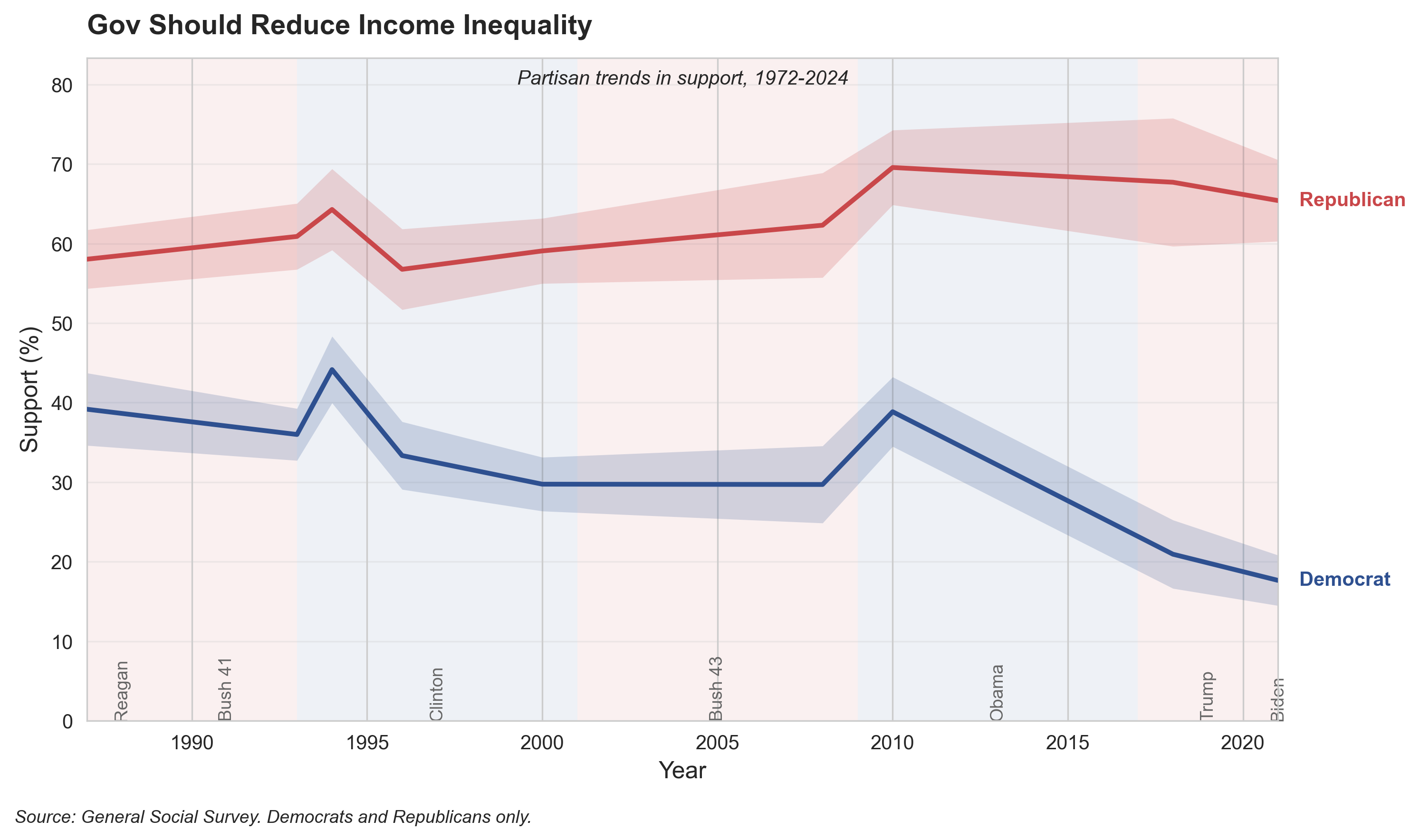

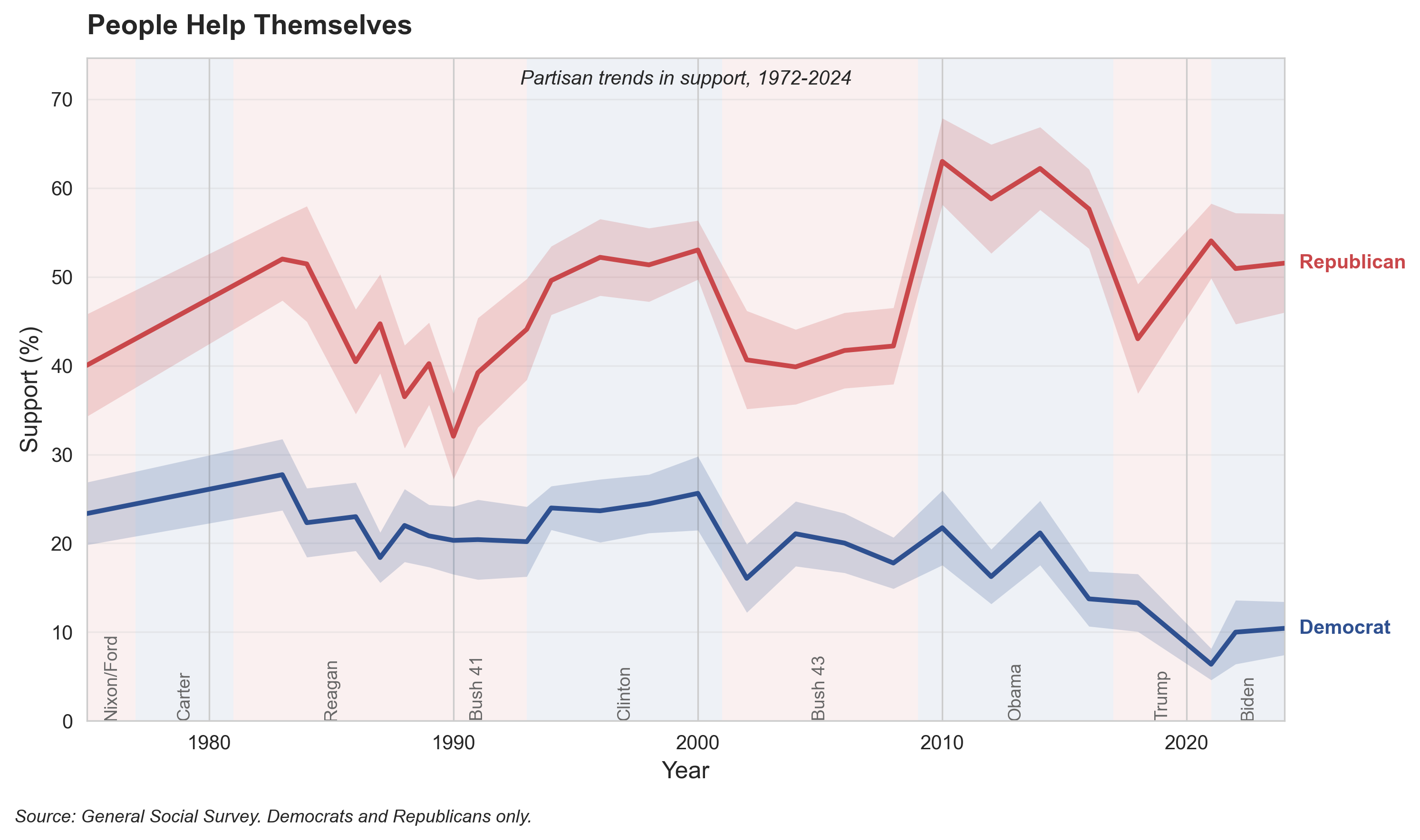

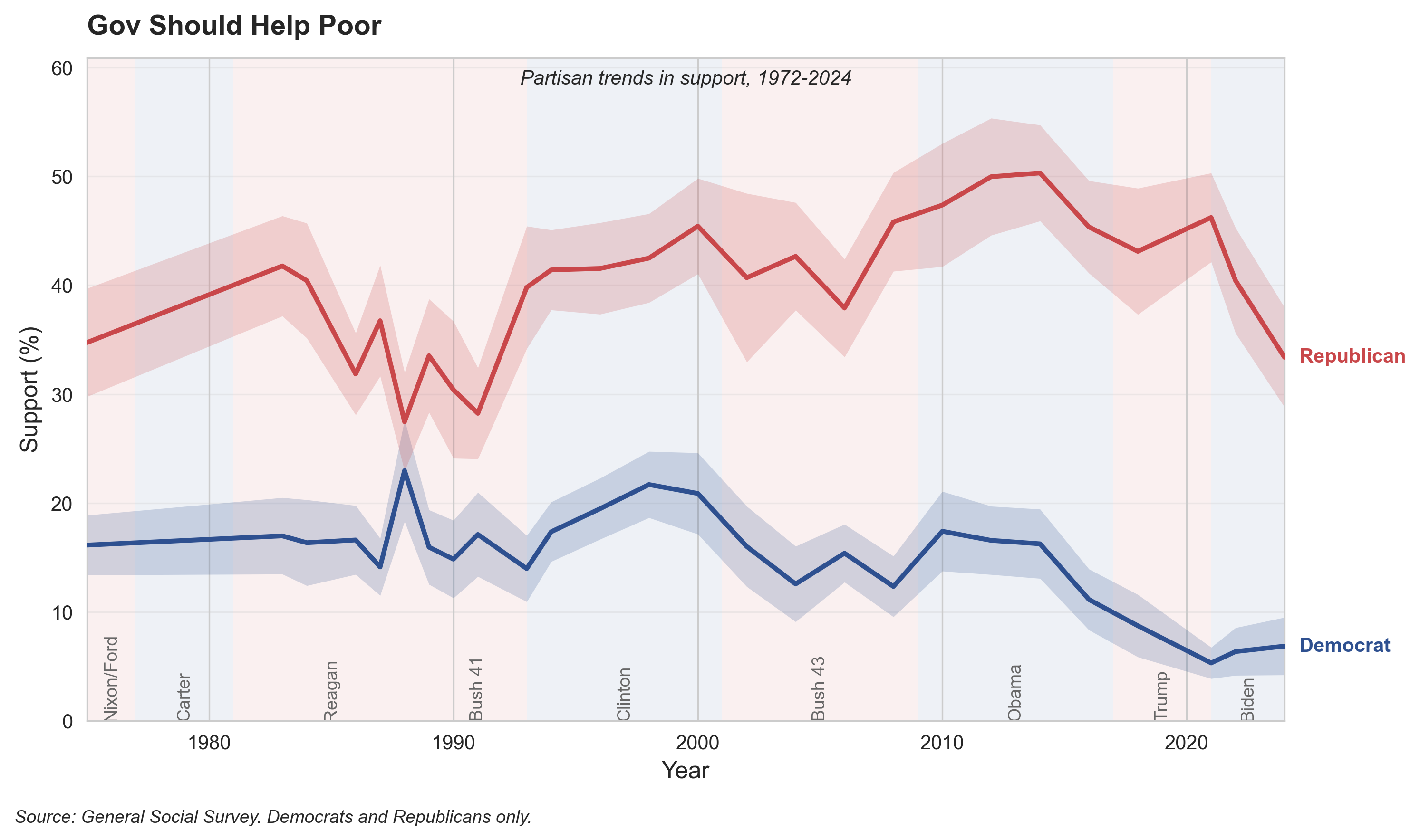

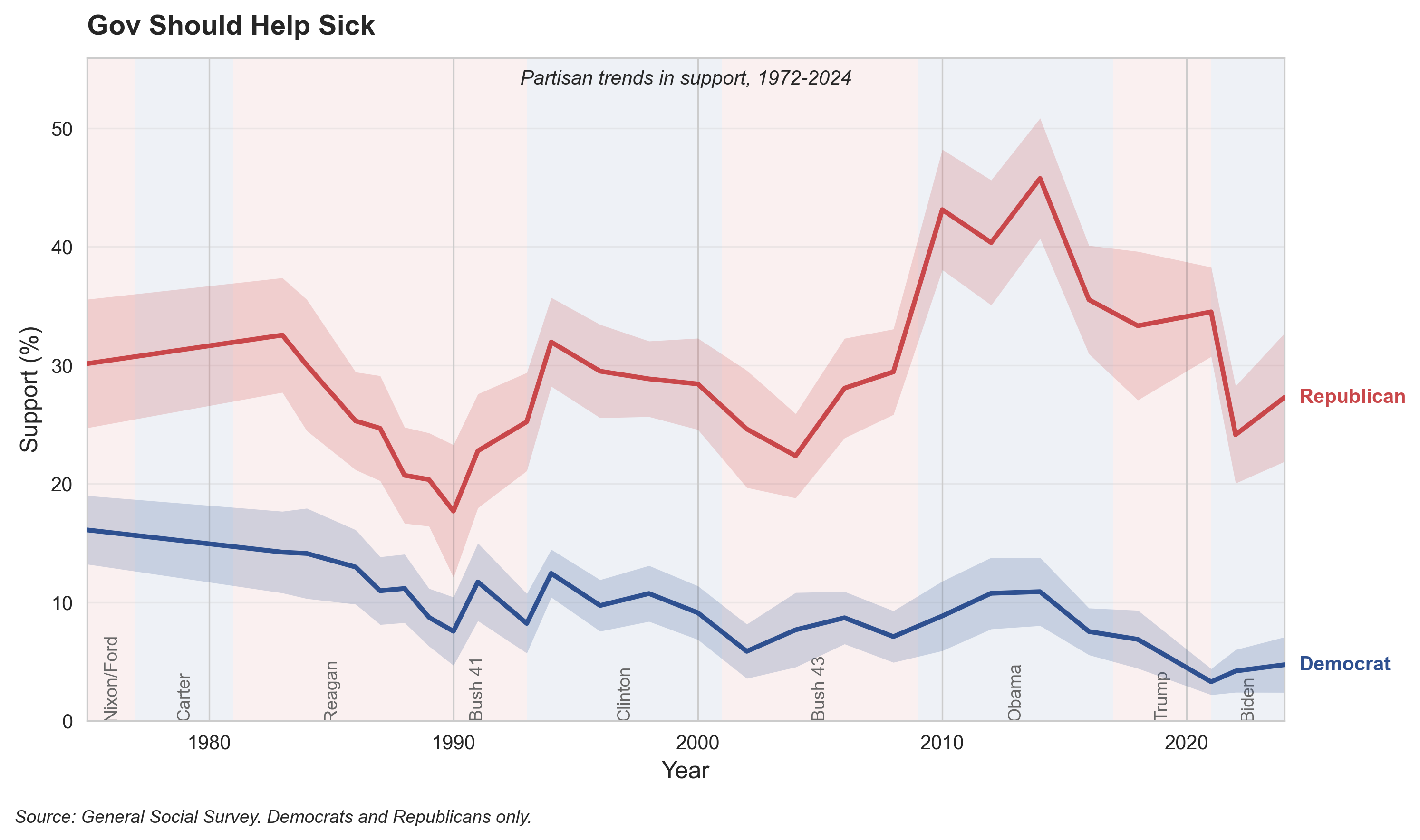

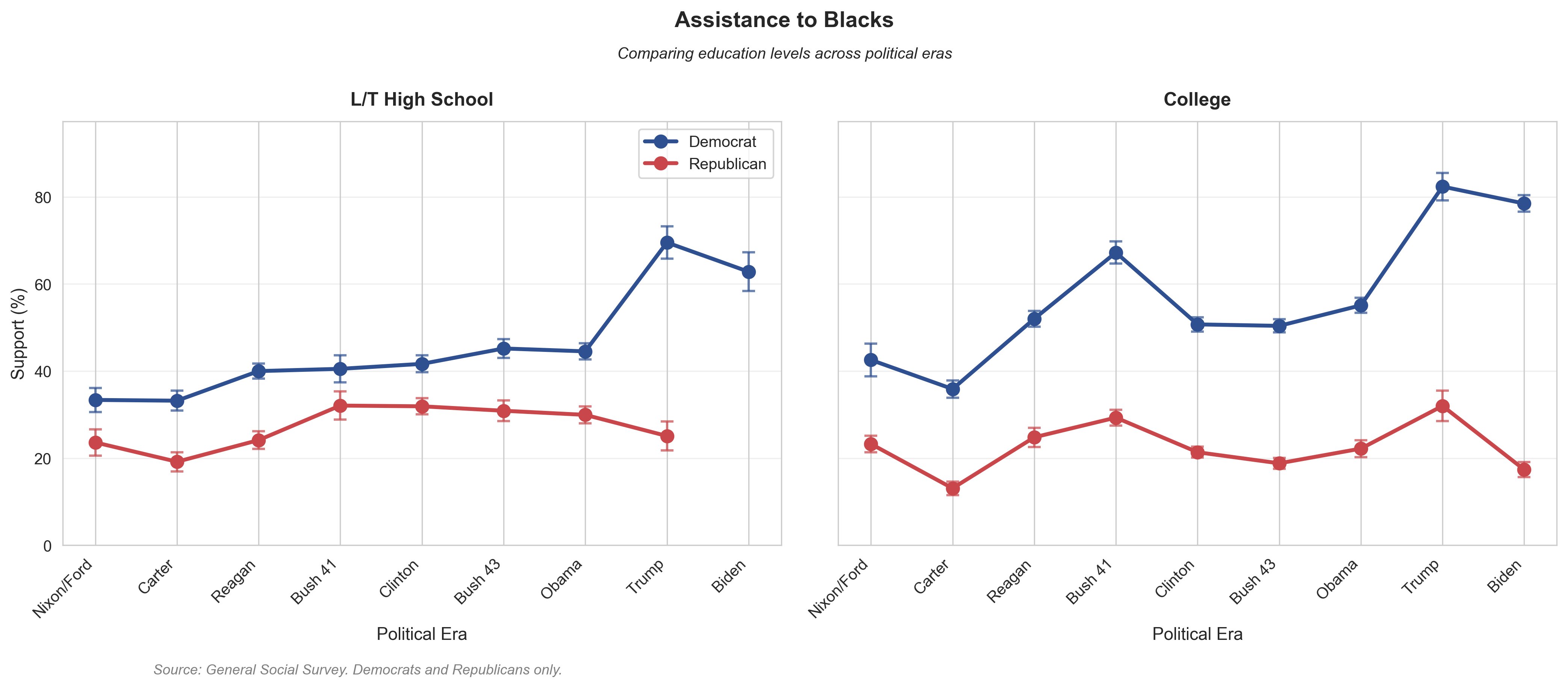

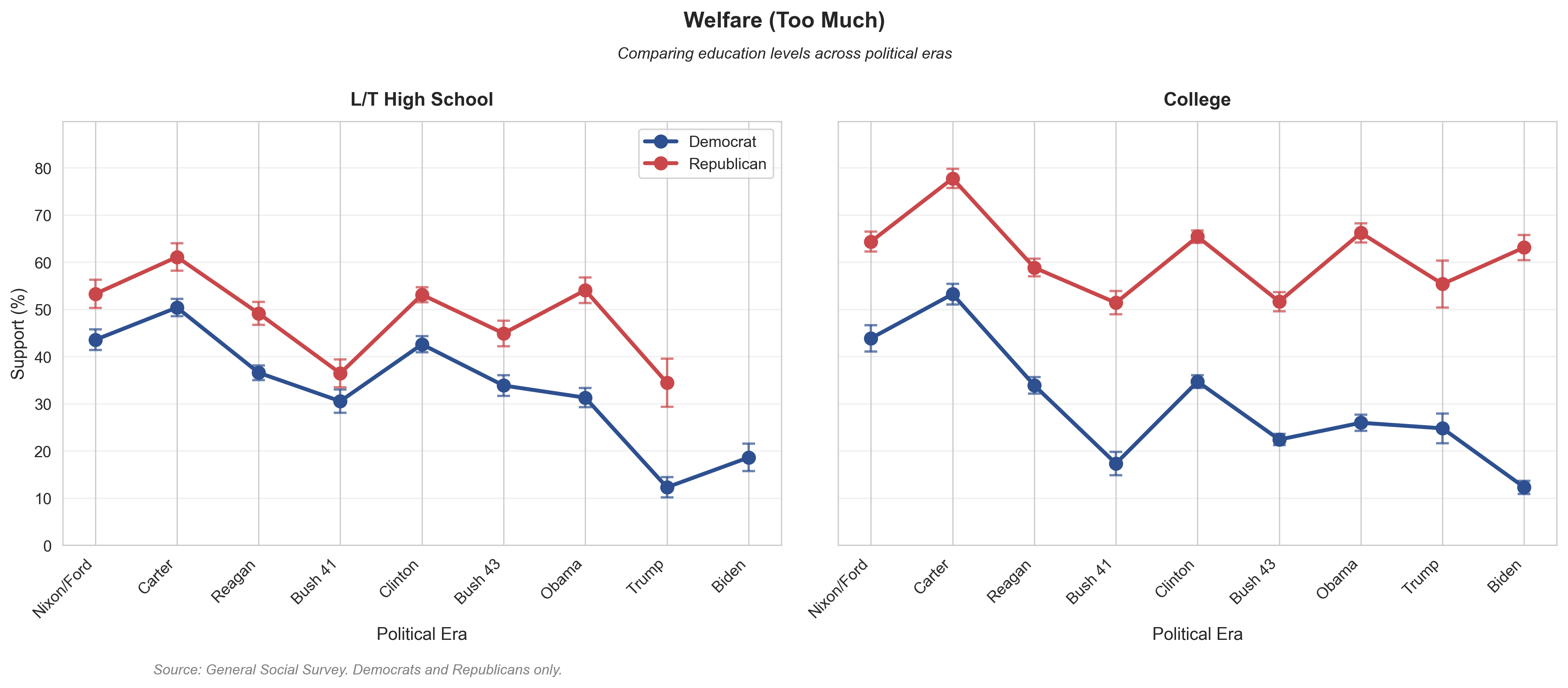

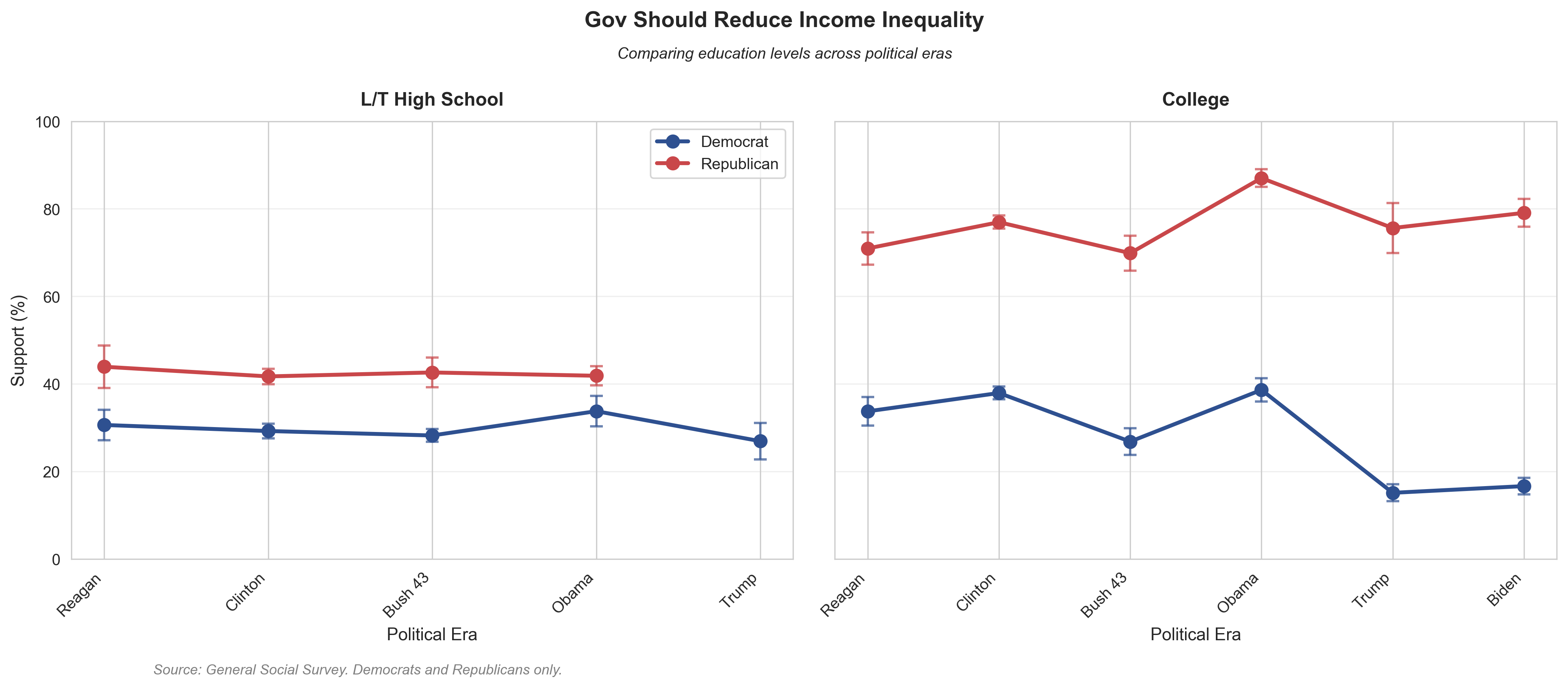

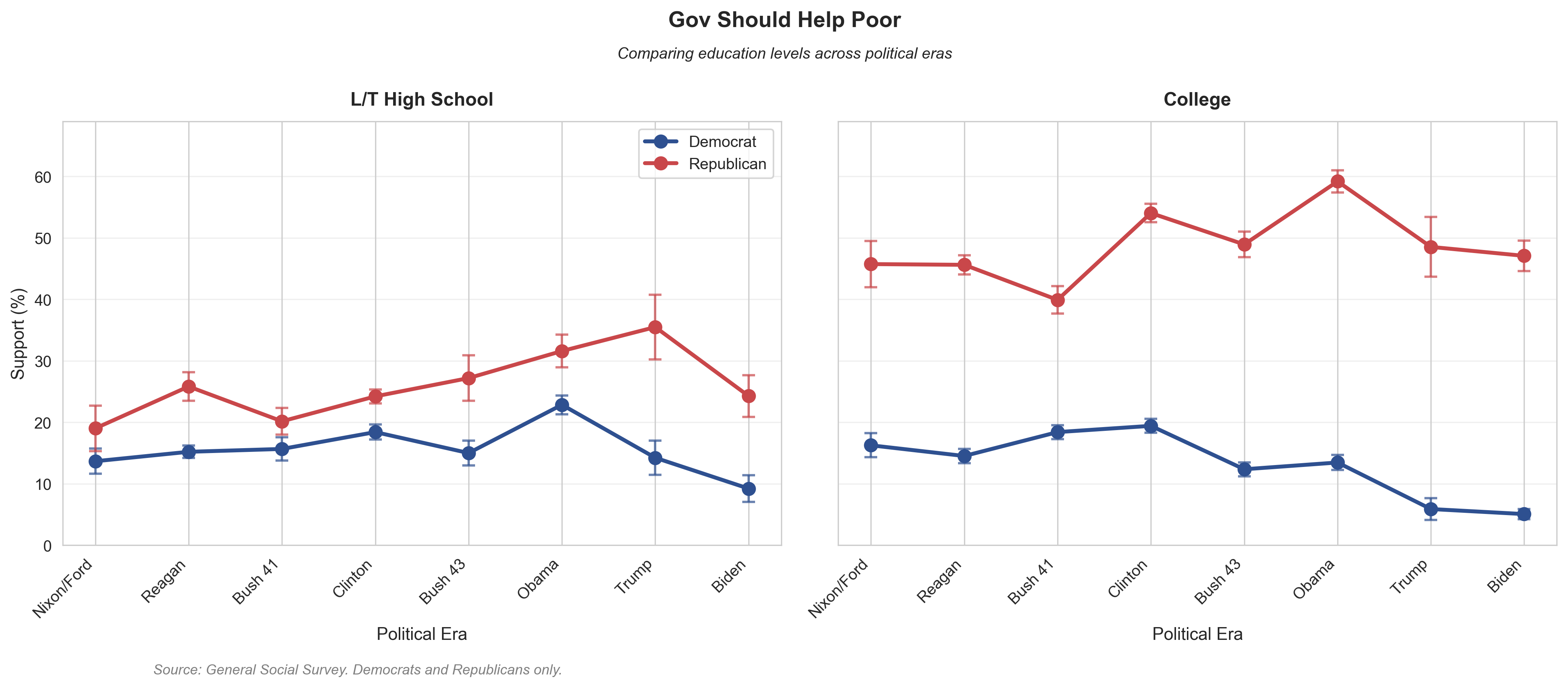

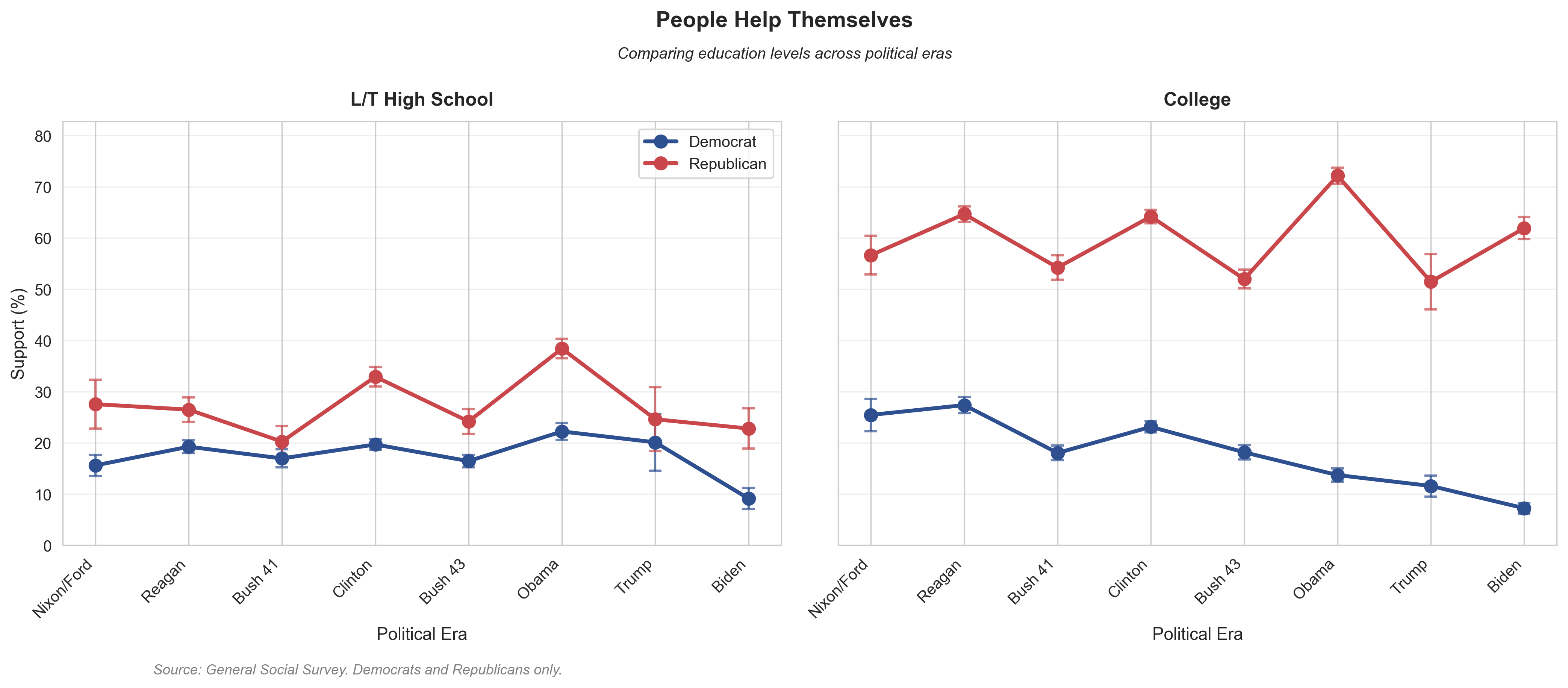

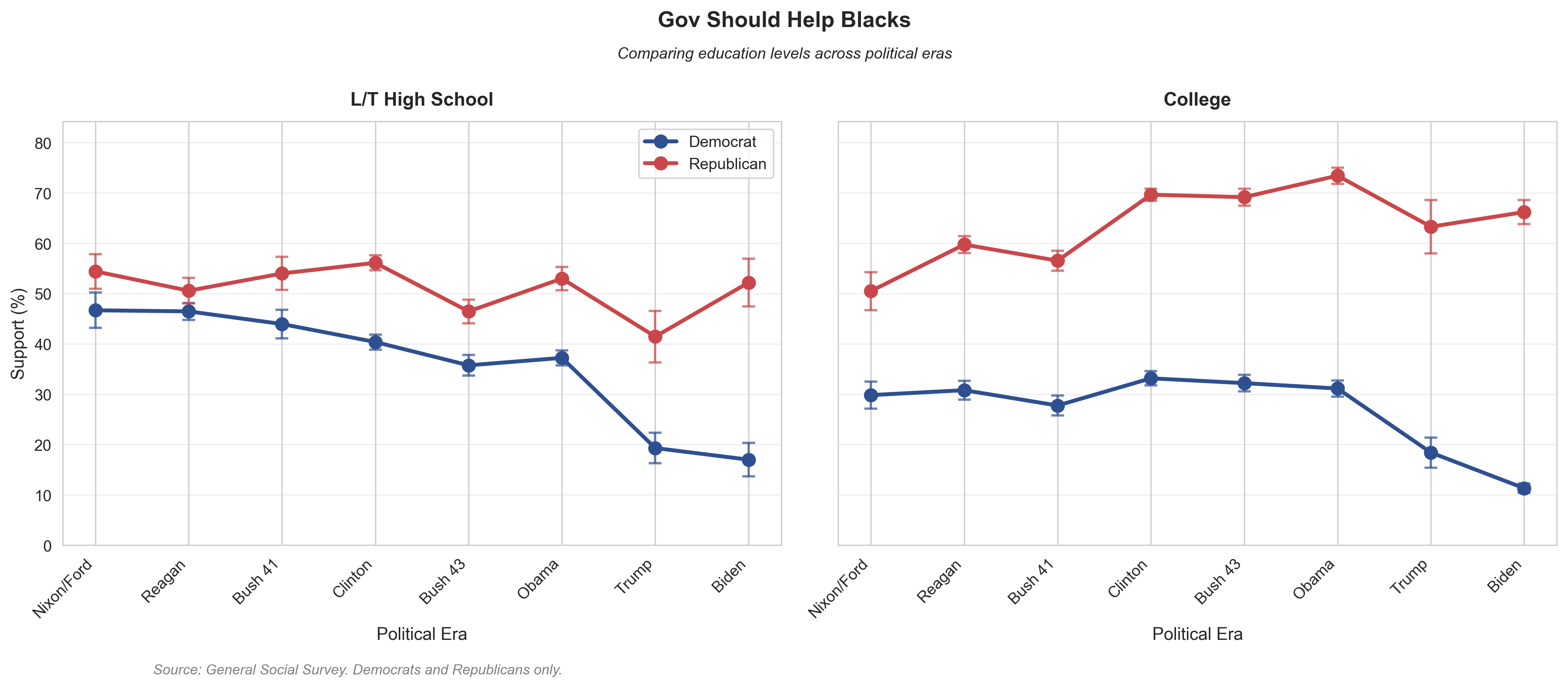

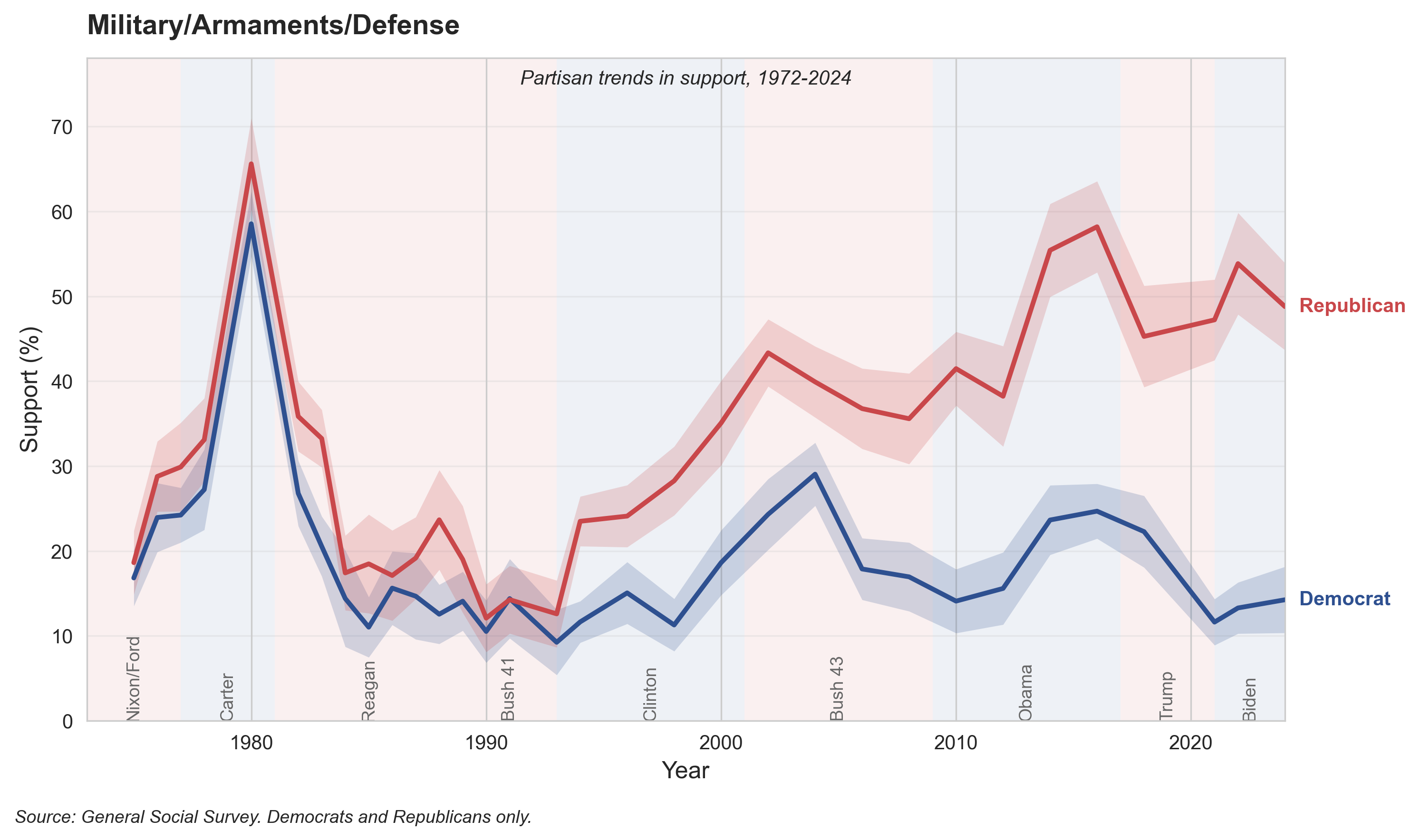

Using five decades of General Social Survey data (1972-2024), we document the emergence and intensification of partisan divides in federal spending preferences and views on government intervention. We analyze 22 distinct spending priorities and government role questions, revealing three key patterns: (1) sharp polarization on race-related and welfare programs, with gaps exceeding 40 percentage points by 2024; (2) education-based amplification of partisan differences, particularly among college-educated voters; and (3) diverging philosophies of government, with Democrats increasingly supporting active intervention while Republicans emphasize self-reliance. These findings suggest that partisan conflict over the federal budget reflects deeper disagreements about the fundamental role of government in American society.

Keywords:partisan polarizationfederal spendingwelfare stategovernment interventionpolitical eraseducational realignment

Social Security: Bipartisan but Declining#